This Is Who We Are

A Cautionary Tale about the Tall Tales We Hold Dear

Reading Time: 15 minutes

The Shooter Hypothesis

One of the amazing books I read last year was Cixin Liu’s The Three-Body Problem. It’s a landmark of science fiction wonder. A gobsmacking achievement. Heady, trippy, profound, it left what will surely be an indelible mark on my psyche. But this, dear friends, is not a GoodReads review.

There’s a section in the book that lodged in my dome. It resonates with this emerging thread about Slipstream Attuning. This parable within the novel brings to light how we come to our beliefs. Like the Blind Men and the Elephant and Plato’s Cave parables, it underscores how we build a worldview based on flawed frames, and fall into the slipstream behind them.

Here’s the “Shooter Hypothesis” parable from The Three-Body Problem:

In the shooter hypothesis, a good marksman shoots at a target, creating a hole every ten centimeters. Now suppose the surface of the target is inhabited by intelligent, two-dimensional creatures. Their scientists, after observing the universe, discover a great law: “There exists a hole in the universe every ten centimeters.” They have mistaken the result of the marksman’s momentary whim for an unalterable law of the universe.

It’s a cautionary tale. After reading it, I was re-attuned to some beliefs I’d held that were built on fallacies. It’s a call to be wary of making permanent any assumptions.

It reminds me of a little parenting reframe I offer my kids. When my seven-year old son, for example, builds his LEGOs, sometimes he gets stuck and can’t find a piece. Before I offer my help, I tell him: first, stand up, close your eyes, spin in circles for five seconds, then sit in another chair. Then, you’ll find your missing piece.

The “Shooter Hypothesis” had me spinning in circles too, re-looking at the landmarks within the stories I was told as a kid, wanting to dismantle them like LEGOs and build them anew.

Darling Landmarks and the Truths They Hide

I’m a proud born-and-bred New Yorker. I graduated college, backpacked Europe, and entered the NYC workforce just weeks before the 9/11 tragedy. It was an abrupt wake up to the realities of the world, to say the least.

9/11 served as a galactic shift of perspective for me. America wasn’t a bubble in a chaotic world. New York wasn’t just the high-energy playground that it had been in my teenage years. Instead, it was the seat of a geopolitical struggle. It was the center of a global story of domination and suffering. There were factions on the world stage that wanted New York’s and America’s stature cut down to size.

9/11 was for naive-me a lifting of the veil. It forced a curiosity that still remains:

What stories have I been told? What frames and foundations have been built in my mind from those stories? What organizing principles evolved from those frames?

I went digging for more darling, dubious narratives that had become my organizing principles. I found new wrinkles everywhere in the tales I’d been told, in the conceptions I held. They weren’t that hard to find either, thanks to the labor of some of our best and brightest truth-seekers.

I suppose this is growing up: taking a fresh look at the narratives organizing our young minds — whether it’s the tooth fairy, Santa Claus, Christopher Columbus, or the American Dream. Moving to the other side of the table, as it were, to find the missing piece of the truth. What’s more, it’s about sitting with those truths, being able to hold it in our frames. Or, as Resmaa Menakem wrote:

All adults need to learn how to soothe and anchor themselves rather than expect or demand that others soothe them. And all adults need to heal and grow up.

The narratives position a lens through which we see a limited view of our world and ourselves. That view determines the choices we have, the decisions we make. And like that it defines who we are, on a daily basis.

A narrative has consequences. Particularly — and most importantly — when that worldview either leaves out major sections of our history, or vilifies whole populations of our communities.

Here’s philosopher Charles Eisenstein taking it to its beautiful meta-conclusion:

If we want to serve peace and wellbeing for all people, a world of healing where society and all the beings on this planet are moving toward greater wholeness, we’d better make sure that we're telling the right story.

What Does The Statue of Liberty Stand For?

When I was younger, I felt the Statue of Liberty was a welcome beacon of hope and freedom on my shores. It was about the aspiration of the American Dream. It signaled the safe space of opportunity and autonomy promised by our founding documents and lasting institutions.

The frame I had about this monolithic landmark was specific. It was about our nation’s inception. We rebelled from unjust monarchic rule. We had a cherished alliance with France. We threw off the yoke of the British. And its resonance into modern day was that America was now an open door, a beacon on a hill.

Give me your tired, your poor,

Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free,

The wretched refuse of your teeming shore.

Send these, the homeless, tempest-tost to me,

I lift my lamp beside the golden door!

That’s the familiar refrain of The New Colossus on a plaque on the Statue of Liberty. It cements the hero and savior myth that Liberty burned into my psyche as a kid.

The kicker is, the Statue of Liberty was meant to be an homage to the end of slavery.

That truth might not surprise at this point. It might even be common knowledge. But even just a decade ago, it was barely known.

The Statue was the conception of a famous French abolitionist named Edouard de Laboulaye. He partnered with Frederic Auguste Bartholdi, the sculptor who built the Statue. They conceived of the landmark as a shoutout to the Americans’ abolition of slavery, the end of oppression. The initial concepts had Liberty holding broken chains in her hand.

The American financiers who helped bankroll the Statue in the late 1800s didn’t want the landmark to broach the topic of slavery. They forced the conceptual pivot that stands today. They’d made fortunes off of the institution of slavery after all. And for over a century the U.S. Park Service (the federal agency tasked with hosting and educating the public about the Statue) obfuscated that major detail about the intended meaning of the Colossus.

As a protocol, the truth of the Statue’s intended meaning was kept hidden. Thanks to the research and advocacy of Dr. Joy DeGruy and others, it’s now a part of the Park Service narrative. It’s no longer hidden.

Nor is the detail that the Statue of Liberty has feet shackled in broken chains.

Of course, most visitors to the Statue wouldn’t ever see the feet. They’re on top of a mammoth pedestal way above eye level. Out of sight, out of mind.

The Statue of Liberty’s origin story and intended meaning were hidden for over a century. A beacon story emerged in its place, to light the way to a freedom tale that was paper thin. For without acknowledging the dark shadow of slavery at its core and the legacy of oppression that’s persisted through American history since, what good is that beacon? If you lift the veil of that paper thin tale, what is left?

As John Michael Greer wrote:

American history can be usefully described as a sequence of attempted journeys toward distant shining cities that do not and cannot exist.

Six Words That Define Us

On January 6th rioters stormed the United States Capitol. Incited by President Trump and by Republicans supportive of and benefiting from Trump’s delegitimizing of the fair and free election, they committed a horrifying act of violent sedition.

In the wake of that day’s trauma, there were morale-boosting speeches by politicians across the country, President-Elect Joe Biden included.

The common rallying cry I heard and read is something on the order of:

This is not who we are.

At face value, these six words are meant to soften the edges of a fraught day, to mollify the trauma of what was witnessed. It’s meant to put the acts at a distance so that the acts can be turned down and condemned. The words are a needed solace, yes. But they rubbed me wrong when I heard them. It felt patronizing. It felt thin. It felt like a bit of an outright lie.

This is not who we are.

Let’s do the outlaw move and really sit with those words and their meaning. For as Douglas Rushkoff wrote:

To suggest we slow down, think, consider… is to cast oneself as an enemy of our civilization’s necessary acceleration forward.

Let’s slow down and marinate in those six words. “This is not who we are.”

This is exactly who we are. Not we, like you and me, and many well-meaning educated folks reading this necessarily. But yes we, the royal We, the American We.

America is exactly the white supremacy and violence that we witnessed on January 6th.

America always has been the white supremacy and violence that we witnessed on January 6th.

For whole communities of folks in America, this country’s systems, ruling classes, and organizing principles are exactly the white supremacy and violence that we witnessed on January 6th.

This is not who we are.

It is exactly who we are. It’s the persistent legacy of America’s founding. And if we owned that fact as a nation — with all the necessary reckoning and reparation — we might one day be able to say those six words and mean it.

But we will never get to the dismantling of that white supremacy, to the reconciliation and healing that we desperately need, if we can’t acknowledge that the rioters and the open pathway through the barricades that they received are the direct output of a white supremacist system.

Or as Isabel Wilkerson wrote so eloquently in Caste:

In the same way that individuals cannot move forward, become whole and healthy, unless they examine the domestic violence they witnessed as children or the alcoholism that runs in their family, the country cannot become whole until it confronts what was not a chapter in its history, but the basis of its economic and social order. For a quarter millennium, slavery was the country.

America is beautiful, as a place, as a concept, as an ideal. In its brokenness and its striving, America growing towards wholeness is beautiful. And… it’s got this deep, dark system and stain that we would do well to investigate individually and collectively. And certainly not hide it under a 305-foot beacon decoy.

It’s not that President-Elect Biden was pulling the wool over our eyes. He was doing what a good leader or a good parent does: sells us on the hopeful side of things. As poet Maggie Smith writes in “Good Bones”:

Life is short and the world

is at least half terrible, and for every kind

stranger, there is one who would break you,

though I keep this from my children. I am trying

to sell them the world. Any decent realtor,

walking you through a real shithole, chirps on

about good bones: This place could be beautiful,

right? You could make this place beautiful.

We need to strike the right balance between this hopeful beacon campaign and getting a good, close look at the truth of things.

The Bigger the Darling, The Harder They Fall

“Killing your darlings” is a figure of speech in the writing domain. It’s as brutal as it sounds. One of the hard parts of editing your own writing is to cut anything inessential, particularly those sections that otherwise sound like jelly or have dear meaning for you.

The phrase has been attributed to many writers, but I like author Stephen King’s take on it the best. In On Writing: A Memoir of the Craft, he writes:

Kill your darlings, kill your darlings, even when it breaks your egocentric little scribbler’s heart, kill your darlings.

Just like pieces of writing, the narratives we are told, we hold very, very dear. With time, they become a part of the soul of our hometown and homelands and of our own fledgling identities. And like that, they become darling to us.

But if they don’t serve the truth, they must be killed. To edit a piece, we need to weed out with impunity. To grow up, to be a true citizen, we need to weed out the tall tales with impunity.

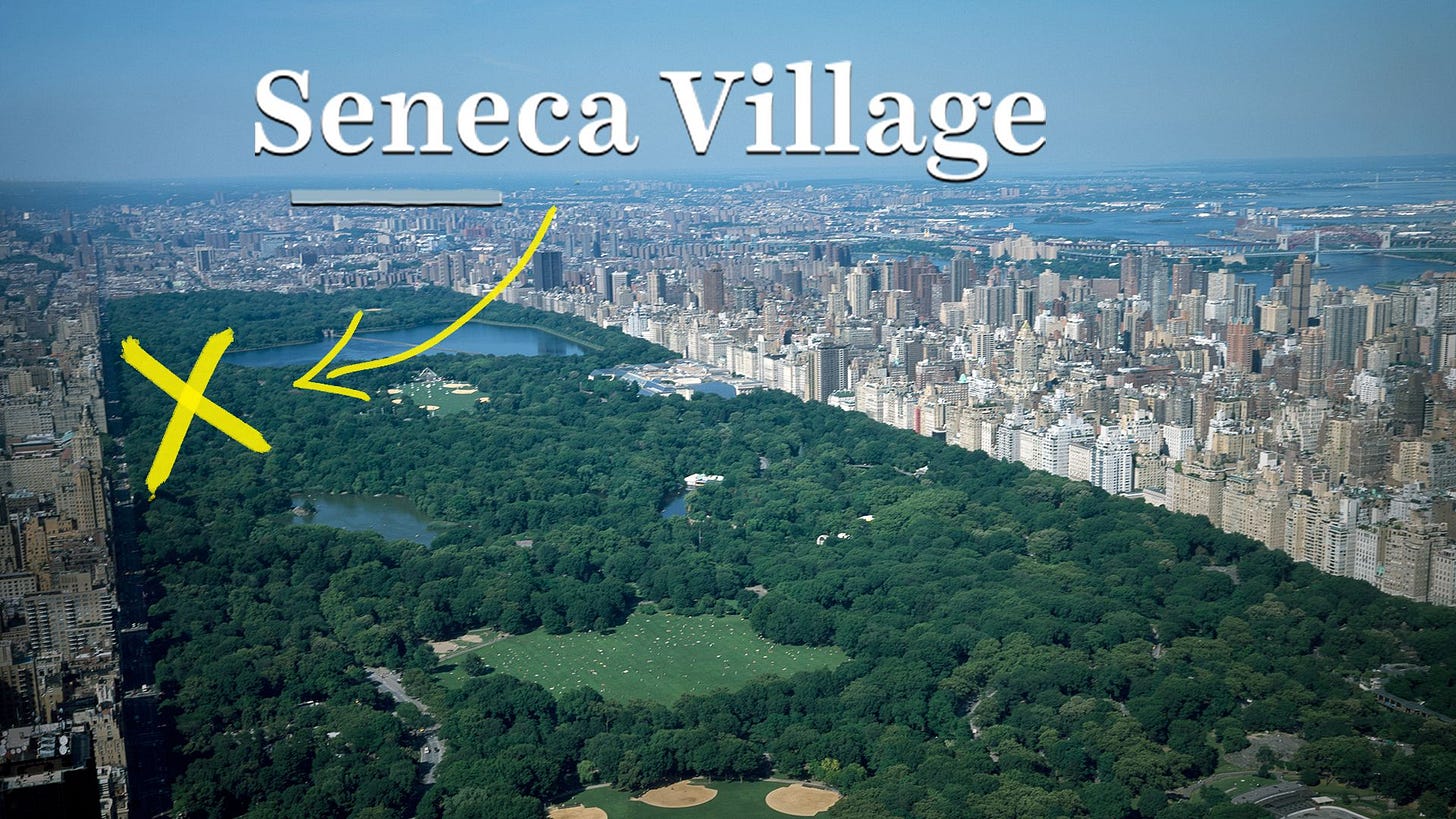

I started to learn about the hidden truths of the city, of our country. Early, big tall tales like the one about Columbus being a “hero” explorer that “found” our land. Less known heartbreakers like the one about Seneca Village.

It was a thriving Black community in New York City in the mid-19th century. Half of the residents owned their homes. The AME Zion Church served as a hub for the community. It was an idyllic enclave removed from the bustle and discrimination of the city. In 1855, the community and their homes were acquired (through eminent domain) and razed to create Central Park, a literal playground for the upper class.

I started seeing these hidden histories, these little darlings, and seeking them out. At first it was uncomfortable to acknowledge that these half-truths had held sway as long as they did.

To this day it’s humbling to acknowledge my privilege and advantage: that I am free to stumble upon these truths by my curiosity, rather than be confronted and traumatized by them every day, as so many are.

It was infuriating to know that the real history had been written over, the hard truth replaced with the soft lie. And it is daunting to know there is no perpetrator in this long con. It’s not as pat as all that. It’s a complex system, not a criminal enterprise.

My first job after college right after 9/11 was located on Columbus Circle. I could see the 42-foot tall Columbus Monument from my office window. Was every landmark in New York City masking a hidden, complex truth? How could I explore this without going down conspiracy theory pathways?

How does one go about killing the big darlings of the narrative of our times to get a better sense of the truth?

Timothy Snyder said it well, on how democracies yield to fascism, Nazism, or communism:

Believe in truth. To abandon facts is to abandon freedom. If nothing is true, then no one can criticize power, because there is no basis upon which to do so. If nothing is true, then all is spectacle. The biggest wallet pays for the most blinding lights.

The so-called selling and spectacle of our landmarks and many of our politicians’ speeches hides a deeper truth about who we are and what organizing principles draft our days. And it’s a dangerous and slippery slope to keep the truth outside of the frame.

Breaking Open the “Overton Window”

Here’s the key question restated: why is it important that I follow my curiosity to these hidden truths? I’ll come at this question through the back window, pun intended.

The “Overton Window” Explained

There’s a theory in the political-science sphere known as the “Overton Window.” Once a wonky, obscure concept intended for think tanks, the idea has grown in popularity over the past decade. In the Trump presidency, the Overton Window has achieved meme status in certain circles. But first, what is it?

Broadly speaking it’s the narrow window of discussion that’s acceptable in the public sphere. The narrower the window, the thinner the array of acceptable ideas and policies. Those within the window then exclude an expansive set of so-called unthinkable and unimaginable nonstarters. If mainstream media and politicians only talk about a certain narrow band of policy ideas for a systemic problem, ideas that are outside that window are perceived to be radical or unthinkable.

In QAnon and sedition times, the Overton Window has been shattered completely: the unthinkable has become the everyday.

Looking at Darling Monuments through the Overton Window

I’m less interested in policy development and conspiracy theories for the moment. What I’m curious about here is the collective development of a narrative and its impact on us as individuals. So, again: why is it important that I follow my curiosity to these hidden truths?

It’s important to look at the hidden truths with sober eyes because what’s hidden becomes our organizing principles just as much as the policies and slogans we toss into the explicit ether. As much as good policies have bent “the arc of the moral universe towards justice,” true change still seems to be elusive.

As Krista Tippett reflected in conversation with Resmaa Menakem:

We changed the laws, but we didn't change ourselves.

We can do policy work until the cows come home, but if we don’t look at ourselves, at the narratives we hold dear, true change will remain illusory.

So, let’s again slow down and continue the thread:

What happens when a half-truth is codified in our narratives? Or when a monument is built — like the Statue of Liberty? What happens to discourse about that truth, about liberty, about our legacy of slavery, when a bold monolithic statue is erected with a paper-thin narrative about liberty attached to it? With the true reckoning buried underground. Here’s a map of the terrain as I see it:

Discourse about the subject shrinks to that narrow, accepted window (i.e., “Yeay America!”). This is the Overton Window; its frame is sketched by the builders and proscribed by the financiers and the limited narrative they want let out. The “system” — consisting of politicians, media, the dominant, social norms of the monied and powered class — continues to brandish the narrative from within the narrow window frame. History books with half-histories are written. Facts outside that frame are labeled radical or fringe and ignored or lambasted. They are not beneficial to the dominant society.

A small fraction of that society engages outside the Overton Window. These grassroots organizers and outlaw thinkers, artists and creatives, philosophers and agitators speak truth to power. Little by little they open the Overton Window to let more light in.

It takes meaningful, disruptive events, leaders and thinkers of integrity, and discerning grassroots groups combining to expand the size of the Overton Window. It’s not, as I once thought, politicians who expand the window to make for more liberated policies and discussions. As was written in 2016:

Many believe that politicians move the window, but that’s actually rare. In our understanding, politicians typically don’t determine what is politically acceptable; more often they react to it and validate it. Generally speaking, policy change follows political change, which itself follows social change. The most durable policy changes are those that are undergirded by strong social movements.

So, again, why is it important that I follow my curiosity to these hidden truths?

Because the issues we as a society face are large and looming and legacies of generations past. The way to change is winding and complex, but I’m convinced it starts with each of us doing our part in sourcing and securing the truth.

The issues that are meaningful to our lives and livelihoods will not be solved by policies that are in place or in discussion in narrow frames now. The crises we face now will not be solved by holding up as sacrosanct the idols and ideals backed by legacies and half-truths.

The more beautiful America we all want will not body forth until we embed the truth in each of our bodies. Healing will begin there. And it will take time. As musician Trevor Hall sang:

You can't rush your healing.

Darkness has its teachings.

The American Three-Body Problem

Cixin Liu’s The Three-Body Problem defies summarization because of its sublimity, complexity, and incredible revelations in the story arc. The concept of the “three-body problem” inspired what has become this thread in this post.

If you’ll forgive the appropriation of that landmark book: America has its own three-body problem. The nation’s long history and its lurching movement towards true liberty and real justice for all has arrived at this turbulent crossroads.

The governing, legislative body that represents the will of the people has work to do getting right with the truths of our history and our moment.

The body politic and social movements have the ongoing work of widening that window frame so that light shines in on the truths of our history and our moment.

The times are urgent, let us slow down.

Because each of us, individually, has work to do in healing our bodies and spirits to be ready to better hold the truths of our history and of this moment. Then, maybe, we’ll find some of our missing peace.

Thank you for reading.

In addition to Martin Luther King, Jr., whose birthday is today, I’m grateful to so many writers, artists, and activists, for their ongoing labor of bringing light on the truth.

I’m learning from them everyday. Some of them I’ve quoted and linked to in this piece. Many others I’ve read or met or otherwise shared time with deserve explicit mention as well. I’ll aim to share a comprehensive list of those in a future post.

-Griff

Thank you for these particular links drawn between the dots you've chosen. Awhile back I heard the term Field of Agreement used to describe the acceptable measure of the tolerance of personal differences, and the tendency to narrow our scope for relational comfort. The Atherton Window scales this vertically. The implied horizontal axis would then likely be shifting values based on the pressures of our time. Seems like the window is widening as the pressure encountered becomes greater, no?

as i read, Trump is leaving the White House, to the Tune of CCR's Fortunate Son...ironic? No, just to unreal again...