Getting Out of the Comfort Zone

Five Mental Models for Creativity and Innovative Thinking

Reading Time: 9 minutes

🧘♂️ Embodied Learning

A few days ago I found myself facedown in three feet of powder. I had a hard-learning ski exploration out of my comfort zone. The upside: it gave me some much-needed insight into the benefit of exploring and thinking outside of standard norms.

In this post, I’ll share a quick anecdote about that experience, and follow that up with five related conceptual frameworks and mental models. These tools will be beneficial for anyone embarking on any type of personal, professional, or existential path of innovation.

⛷️ Out of the Comfort Zone

Over the weekend my dear friend here invited me to ski Highlands Bowl. This is an in-bounds but remote ski area here in Colorado. To get there, you take a lift to the top of Highlands ski area, strap your skis to your back, and hike 45 minutes up a steep knife’s-edge ridge to the summit of a magnificent bowl. Then, you ski through the ungroomed terrain. It’s not “backcountry” but it’s damn close.

Some context: this is my first winter in Colorado, and while I grew up skiing in the Northeastern US, my experience was pretty limited. I’ve skied 25 days so far this winter, close to the total number of days I skied in my life prior. I’m a good skier, not expert. I can shred any blue square, and can hold my own on just about any more advanced groomed slope.

All that’s to say, this Highlands Bowl experience was at my edge, if not beyond. Also, for additional context, there was at least one 11-year old amongst the crowds doing this adventure. So, there’s that.

Hiking up the ridge in ski boots to a 12,400-foot summit with skis on my back was hard on my Angeleno-acclimated lungs. My legs were wet noodles by the time I strapped my skis on to descend the bowl.

From there, the terrain is thick, deep powder through a forest. Not what I’m used to. My northeast upbringing means I’m comfortable in thin snow cover and ice; I’m inexperienced in thick powder. On my way down I fell at least ten times. I’d try to use the pole to help me up and it would slide into the powder all the way up to the handle, giving me no support.

The initial descent into the bowl is steep and technical. This was the most challenging part. And at the moment when the terrain flattened a bit, I felt this exuberance come over me. I let myself go with a hooting semi-barbaric yawp of excitement… and then immediately lost control and fell flat on my face.

It was an amazing and humbling experience. Usually when I’ve skied this winter, I feel capable, empowered, and an incredible endorphin surge as I carve smooth and fast down the mountain. There’s flow, control, elegance.

On the bowl run I felt mostly incapable, a little defeated, panicked and outright tuckered. When I got home, I showered, got in bed, and passed out hard before completing one full breath.

In the aftermath it brought to mind a few frameworks and mental models on this theme of getting out of one’s comfort zone. When we want to innovate our lives or upgrade our processes, what tools and concepts can we lean on for guidance and inspiration?

Here’s five such tools and frames that come to mind:

🪒 ~The Discomfort Razor

☑️ ~ Thinking Inside the Box

🆓 ~ “Jootsing”: Jumping Outside the System

🌊 ~ Blue Ocean Strategy

🆚 ~ Live vs Dead Players

🪒 ~ The Discomfort Razor

The readymade and most impactful learning outcome from this experience was the simple “no pain, no gain” epiphany. Like pushing yourself in a workout, or setting a BHAG (Big Hairy Audacious Goal) for a project, sometimes the best course of action for growth is forced discomfort.

A couple days ago I happened upon writer George Mack’s “Discomfort Razor”:

The more uncomfortable the activity, the more likely it will lead to growth. The more comfortable the activity, the more likely it will lead to stagnation.

1000 uncomfortable hours > 10,000 comfortable hours.

Skiing gets me exercise, an endorphin kick, and an hour or two out in the forests and elements of Colorado. It’s a blessing. But had I just gone out for a regular ski day, would the comfort have led me into this new mental terrain? Would it have enlivened this corner of my experience?

☑️ ~ Thinking Inside the Box

The terrain I skied through is in-bounds. It’s on the ski area map, and it’s monitored by the ski patrol. It’s entirely within the so-called system, though it was at my edge. It’s in the proverbial box.

Think outside the box is one of the chief clichés of innovation and strategy. There’s a time and place — and a hundred tools and tricks — for thinking outside the box to get at a solution.

There’s also meaningful reason to mistrust that adage when seeking creativity, or when confronting the most pressing, systemic crises of our times. As Bayo Akomolafe said at a conference in Kigali:

Thinking out of the box is exactly how the box thinks. We are the boxes we strive to out-think.

What this means to me is that our so-called priors, biases, preconceived notions, and undetected organizing principles are the limiting factors in our own innovation and creative thinking. We can’t think outside the box, when the box is our own minds. That’s not to say leaps of innovation aren’t possible, but sometimes those leaps need to come from a different impetus altogether.

And sometimes there are conditions ripe for innovation within the box. As Anne-Laure Le Cunff writes,

What if innovation could be fostered by thinking inside the box instead? That’s what Systematic Inventive Thinking (SIT) aims to achieve.

When innovating on a product or process, or solving entrenched problems of our society, sometimes working within the so-called confines of the system can bring its own upgrade in creativity. If we assume that the solution lies within the “closed-world conditions” of the system, how might we rearrange the existing properties to force something new and upgraded?

In the Creator Economy, there’s a treasure trove of tools and stacks from which to choose. At any point in the creation of this newsletter, for example, I come up against resistance or edges of growth. There’s an impetus in that moment to reconsider my email service provider, my note-taking system, my sharing and distribution plan. I could replace any part of my process to get at better productivity or greater growth, that voice says.

The thinking inside the box concept strikes a different balance. It suggests that the components of the upgrade are already in play, that innovation will come from working within the existing system.

In other words, stop reaching for the shiny new toy, tool, or concept. Just work with what we already have. It’s an elegant reframe on that old cliché.

🆓 ~ “Jootsing”: Jumping Out of the System

Philosopher Daniel C. Dennett wrote the most eloquent definition of creativity (hat tip to Shane Parrish for sourcing it):

Creativity, that ardently sought but only rarely found virtue, often is a heretofore unimagined violation of the rules of the system from which it springs.

The comprehensive elegance of that sentence is profound. Creativity as a violation of the rules of a system.

I think we’re raised to believe that creativity is a fire, that it is this unbridled force that graces the creative person at the fire’s whim. The muse comes to visit or the muse does not. The creative force inherent in nature likewise is wild, chaotic, unpredictable.

But as the image and quote above depict, there is a process to creativity. Dennett called it “Jootsing” — a fun acronym for “jumping out of the system.”

The process by which creativity and innovation take place must include a clear rendering of the system, its laws and limitations. As Parrish writes:

We can break the creative process down into the following three steps:

Gain a deep understanding of a particular system and its rules.

Step outside of that system and look for something surprising that subverts its rules.

Use what you find as the basis for making something new and creative.

It may not be simple to do, but it is reliable and repeatable.

It’s a compelling variation of the “think outside the box” cliché.

In the writing of this newsletter, I have this competing set of urges. On the one hand, I’m for following my own curiosity, untethered to any expectations. On another, I’m for growing readership and following the so-called rules to do so. On the one hand, I’m charting my own course, and on the other, I’m on the trodden path. Or as I wrote in an earlier post:

Writing is two games — one of authenticity and vulnerability, and one of engineering impact and exploiting the reader’s receptivity — and learning how, when, and why to play each game is the craft.

The rules of the game, we must learn. Once we learn them, we can break the rules in the just-right way that surmounts and subverts the game.

🌊 ~ Blue Ocean Strategy: Make Competition Irrelevant

In a similar vein, one of the most effective strategic frameworks I’ve come across is the Blue Ocean Strategy. It’s “jootsing” for product innovation. And the spirit of it can be extrapolated to any creative endeavor.

The basic premise is that any product or industry has its own system, consisting of a matrix of factors that it competes for, with only mild variations.

Hotels, for example, compete on location, amenities, price, etc. Every single hotel in existence falls on some spectrum of each of those competitive factors, whether you’re the Rosebud Motel or the Four Seasons. Airbnb comes along to provide the same service as the hotel (a place to spend a night outside of your home) but makes the competition irrelevant by not competing under the same framework of factors.

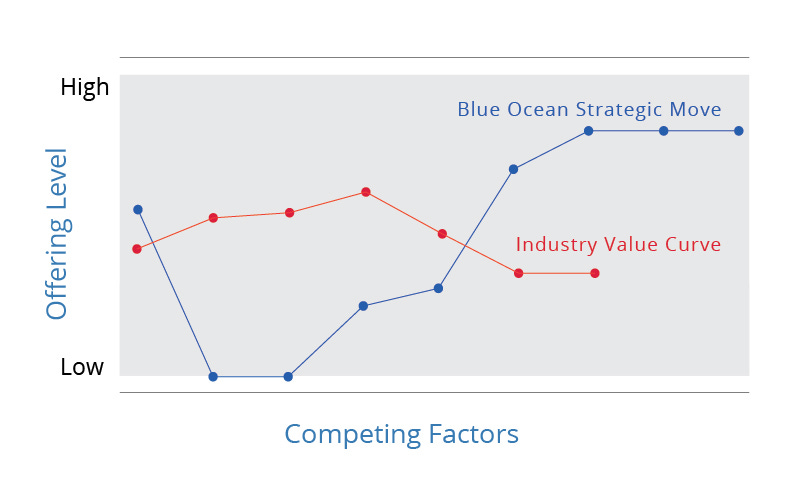

The above image shows the template Blue Ocean Strategy Canvas. The red line and its dots show the industry standard product and its scoring along a variety of competing factors. These are the norms. The industry standard competes in middle-of-the-road offering levels. The blue ocean entrant competes at the very edges to beat out the industry standard and offers elements that are out of bounds for the industry standard. The entrant bucks the system and disrupts the category, thus arriving in a blue ocean of its own domain.

Think of Radiohead. They start out in the early 90s as this brooding rock band with a sublime but standard sound and instrumentation. They start to innovate on their sound. I saw them live, The Bends tour in New York City. I’ll never forget guitarist Jonny Greenwood’s pedalboard and the consortium of sound effects he elicited. They were outcompeting other bands and themselves by taking on a version of tech that was innovative and downright cool.

Fast forward a half a decade, and they release Kid A which is a complete rock departure in favor of sounds reminiscent of jazz, classical, and electronic music. While most bands deliver modulations of their core virtues album after album, Radiohead pulls a more total shift. We will never know, but I wonder: if they hadn’t embarked on their ongoing breadth of innovation, would they have reached the heights they have?

The key question for Blue Ocean Strategy is, do you take the industry norms as a cold, hard given, or do you redefine them in your favor?

For more on Blue Ocean Strategy, check out: How to Be a Blue Ocean Strategist in a Post-Pandemic World

🆚 ~ Live vs Dead Players

This skiing experience brought to mind a profound framework that Peter Limberg of The Stoa shared. It’s called “Live versus Dead Players” and it was developed by Samo Burja.

In Burja’s essay he considers a “live player” any individual or group that is effective, broadly speaking, at doing new things. The person or group can go off-script, create new ideas, go out of bounds. They are “live” in this regard because they can emerge into the new.

Live players are needed for creating a thriving and sustainable society. Players incapable of building or maintaining a process without the strict frames, boundaries, and unrelenting code of the systems are, in Burja’s terms, ‘dead’.

Stark classification aside, the frame applies well here. Any innovation or creativity requires birthing something new, regardless of the tool or mental model undertaken. Rigid adherence to form, rules, and function of a system won’t body forth the elegant and beautiful solutions we need.

Rigidity like that can’t foster the flourishing. Complex systems emerge into transformative shifts by embracing the new, the unknown. Rigidity disallows the out of bounds.

That’s all for now. Thanks for reading!

-Griff

wonderful read! love the 'thinking in the box' very much in line with the vedic view. thank you for the inspiration!

quantum society is blue ocean - i love it !!